The Church of SS Cyriac and Julitta

The double dedication of this church always arouses interest. St Cyriac and St Julitta were a three-year-old child and his mother who were martyred in about 304 AD, during the Roman Emperor Diocletian's terrible persecution of the Christians. One legend has it that Julitta, before being crucified for her faith, was brought before the governor of Silicia for questioning. Her little boy had been placed upon the governor's knee and during the proceedings insisted upon telling the governor that he was a Christian, whilst also boxing the governor's ears. This infuriated him so much that he flung the child to the marble floor with such force that Cyriac died instantly. His feast day is kept on June 16th or July 15th - the latter favoured by the Eastern church. Only a handful of English churches are dedicated to him: Newton St Cyr's (Devon) has the same double dedication and South Pool (Devon) is dedicated to SS Nicholas and Cyriac. St Cyriac is also patron of the splendid church in Lacock, Wiltshire.

It is worth taking time to walk around the exterior of the church and also to stand back to view it as a whole. The western tower, which rises 72 feet above the ground, is a noble example of the skill of its medieval architect and builders. Its height is accentuated by the lack of a clerestory, which makes the body of the church look low in comparison. Money was bequeathed towards the tower in 1493 by William Larde and John of Dullingham and, in 1504, by John Meede; so we can assume that building continued into the early 1500s. Flints, cobblestones, dressed limestone and Tudor bricks may be seen amongst the materials in its walls and there are Tudor bricks in its chequered base-course. Notice also in the walls the small square put-log holes through which the wooden scaffolding was placed when the tower was being built.

The lower section is square and is strengthened by sturdy buttresses. At the tops of its four corners are the bases of the tall pinnacles which once crowned them. Behind these the corners are cleverly chamfered in order to join up with the base of the handsome octagonal belfry stage, which has slender and elegant buttresses, resting upon carved stone corbel heads, at its corners. Each of the eight sides of the bell chamber is pierced by a two-light window, divided horizontally by a transom, beneath which it is filled in with bricks. The tower is crowned by flushwork panelling in flint and stone, which must have looked magnificent when its battlements and pinnacles were complete.

A prominent staircase-turret may be seen on the north-east side, reaching the full height of the tower and having its own flushwork parapet. Above the 15th century west doorway is the partly-blocked three light west window. Its upper parts now have wooden mullions and tracery, behind which are the original stone ones, visible from the inside. Octagonal upper stages are a feature of several church towers in the area. We see them at nearby Burwell, at Wood Ditton, Cheveley, Sutton, Great Shelford and, of course, in the lantern at Ely Cathedral. But it is hard to beat next door St Mary's which starts square, becomes octagonal and ends up sixteen sided!

The body of the church is a large rectangle (55 feet long and 40 wide) divided into a nave and north and south aisles. To these an eastern sanctuary and north and south transepts have been added making (with the tower at the west end) the plan of a rather eccentric cross. The exterior walls are faced with gault bricks and are strengthened by stone buttresses at the corners (above which are pinnacles at the eastern corners of the aisles). The walls throughout terminate with embattled parapets. The church is well lit by windows of two, three and four lights, which have the most basic 'tracery' possible. The mullions were originally all of wood, earning the epithet 'Carpenter's Gothic', but they deteriorated badly and restoration has been largely in stone to prevent decay. The style could be called Perpendicular at its simplest, with only the three-light windows in the east wall of the sanctuary and the south wall of the south transept attempting to reflect the medieval original.

Inside St Cyriac's

Think for a moment of the previous church that was here. Something of its brilliance can be imagined from the terms of the will of Thomas Elles of Reach, written in 1517: "... to buy a cross for the church of St. Ciric with Mary and John silver and gilt to be borne in procession on the high feast of the year £20. To St. Ciric's church £20 to buy a cope and a vestment. To buy a Monstre of silver and gilt to St. Ciric's to bear the Blessed Sacrament on the high feasts of the year £4".

About sixty years before the medieval church was demolished William Cole found it changed, like St Mary's, in obedience to the rules of the Anglican liturgy. Between the nave and chancel was a screen, above which were the Royal Arms, the Lord's Prayer, Creed and Commandments and a Text from Joel 2:17. From the original church furnishings there remained old stalls in the sanctuary as well as a piscina.

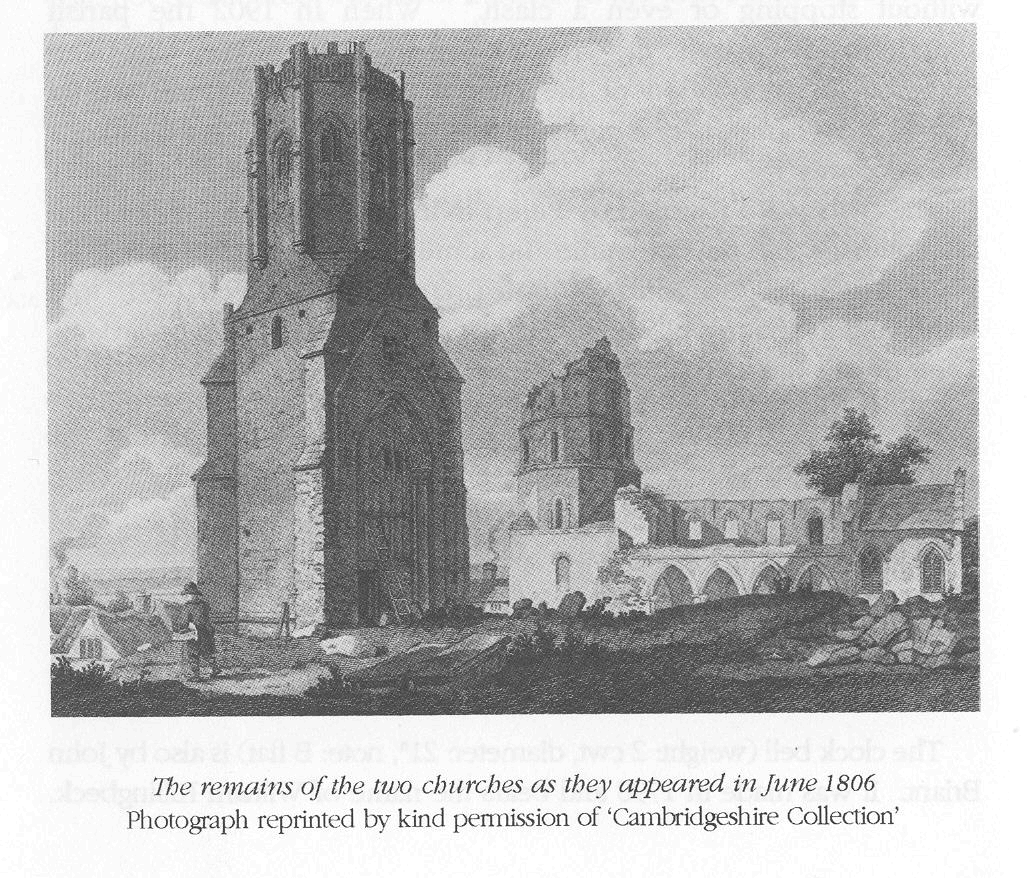

The present church is a fascinating period-piece of 1806 designed by Charles Humfrey, a Cambridge builder's son. He studied in London under the architect James Wyatt, who was one of the first to revive interest in gothic architecture. In Cambridge, Humfrey built the Georgian villas in Maid's Causeway opposite Midsummer Common and the elegant Park Terrace overlooking Parker's Piece, as well as the little tower of St Clement's church in Bridge Street, dedicated to William Cole. He was also the architect for the vicarage at Swaffham Bulbeck. Humfrey's choice of a simple form of 15th century Perpendicular architecture for St Cyriac's was advanced for its day, coming at least 35 years before the Gothic Revival began to transform 19th century architecture. It is light and airy and inspired more by the frivolity of gothic than by its solemnity. It scarcely deserves the epithets 'debased' and 'ugly' subsequently hurled at it by the ecclesiologists, with their preference for the more sombre Early English and more 'correct' Decorated styles.

The foundation stone of the church was laid on May 28, 1806 by John Peter Allix. The plan was for a preaching auditorium with deal box pews round the walls and free-standing bench pews in the centre. Its purpose was to accommodate large congregations who came to hear the Word from its pulpit and to attend Divine Service of the Established Church. At that time the Holy Communion was a rare and special event which was celebrated three times a year, so this building, unlike its medieval predecessor, had no need for a structural chancel. Here only a small sanctuary recess (10 feet by 14 feet) has been provided, separated from the nave by a broad and shallow arch.

Similar arches on the north and south sides lead to the small transepts. The south transept has a door from the outside, possibly for the Allixes to enter privately into their family pew. The plaster ceilings are almost flat and dividing the aisles from the nave are not arcades, as we might expect in a gothic church, but two huge, moulded, wooden piers each side reaching to the roof. The matching half piers against the walls are of stone and parts of them may well be medieval work reused.

The western gallery, with its simply-panelled front, is supported upon six columns. Most churches of this date had galleries for singers or an amateur village orchestra to accompany the singing. A notice beneath it, however, tells us that this gallery, erected in 1819, also provided "50 free and unappropriated sittings" at a time when most pews in the body of the church would have been owned or rented by the families which occupied them.

The little sanctuary at the east end has now lost its communion rails (taken to Reach church "by Mr. Sargeant in a hand cart" recorded the vicar) but the notches into which they fitted may be seen in the great arch. The panelled wainscoting remains, however, as well as the Ten Commandments painted on the wall each side of the east window and the Lord's Prayer and the Apostles' Creed on the side walls. The present Communion Table was brought in 1992 from the classical parkland church of All Saints at Nuneham Courtney in Oxfordshire. It probably dates from 1764 when that church was built.

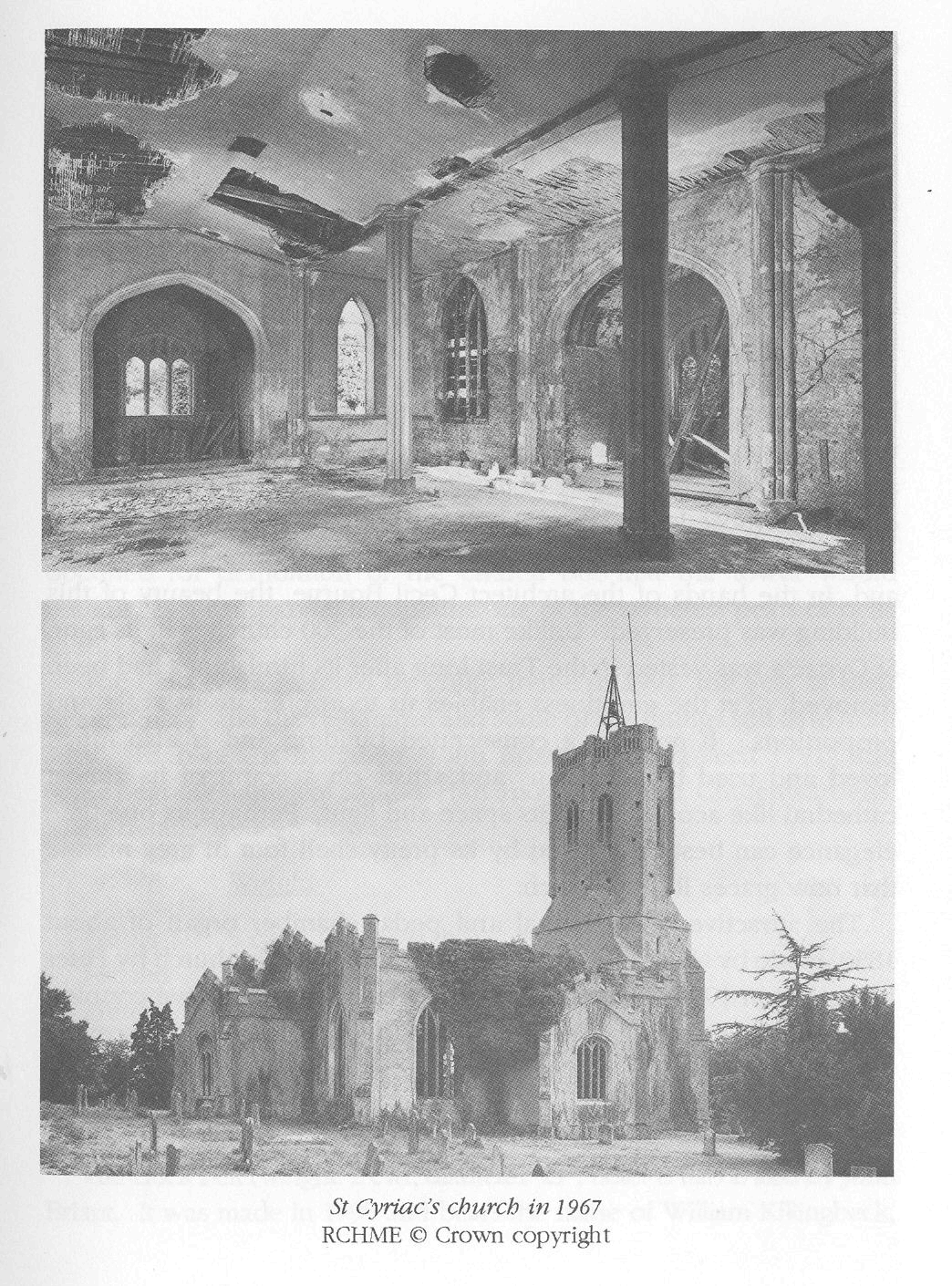

Now picture this building as Olive Cook found it in 1956. "A scene of indescribable desolation awaits him who pushes open the cracked and blistering door ... the neat box pews are all broken; the doors lie in fragments or dangle at harsh angles from severed hinges. Glass from the windows strews the floor, wall tablets, loosened and cracked by damp, have crashed down, and through the eastern end, open to the sky, a hoary tree has pushed its heavy branches". Wall tablets, alas, not considered worthy of transfer to the brave new church next door and whose legend we shall never know.

In the 1970s The Churches Conservation Trust came to the rescue and, in the hands of the architect Cecil Bourne, the beauty of this building was preserved. Unlike most of the 300 churches in its care, St Cyriac's was vested in the Trust long after its furnishings had been removed. Yet the emptiness enables us to appreciate its scale and proportions. It remains a consecrated building and is also much loved and used by musicians and artists on account of its almost cathedral-like acoustics and its space and light. Perhaps its one-time elegance can best be evoked by its pretty shell font in grey marble that now graces Reach church.

The attractive, two manual and pedal chamber organ of about 1850, made by Courcelle, was restored for use in this church by Peter Bumstead in 1996. The pedals have an unusual sub-octave coupler. Interestingly, Courcelle, like the Allixes, was of Huguenot descent.

"One of the sweetest peals of bells in this county"

The tower contains a ring of six bells. When the spire of St Mary's was damaged in 1779 the bells were stripped out of both towers (five from St Mary's and three from St Cyriac's). One of the St Cyriac bells was engraved MARIA. They were melted down and recast as a ring of six by one of the finest bell-founders of his day - John Briant of Hertford - and re-hung in St Cyriac's in 1791. On November 5th the Cambridge Chronicle reported: "At the opening of the new peal of six bells at Great Swaffham in this county, on Monday last, very great praise is due to the Soham Youths, who raised the Bells and in a very superior stile of ringing rung the following peals, viz. Plain Bob, Treble Bob, Court Bob, and Double Bob, and fall'd them again without stopping or even a clash". When in 1902 the parish abandoned St Cyriac's, the vicar explained that a faculty had been obtained for demolition of the church but that the tower would remain "as a campanile: it contains one of the sweetest peals of bells in this county".

The bells were restored by Philip Irvine in 1991, the year of their bi-centenary, and the bell frame and some of the fittings still date from 1791. Each bell is inscribed "John Briant Hartford Fecit 1791" and some bear the names of Samuel Hart and John Nunn, Churchwardens. Their details are as follows:-

| Weight | Diam. | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treble | 5 cwt 0 qr 0 lb | 27 7/8" | E |

| Second | 5 cwt 1 qr 0 lb | 30 1/8" | D |

| Third | 6 cwt 0 qr 0 lb | 32 3/16" | C |

| Fourth | 6 cwt 3 qr 0 lb | 33 3/8" | B |

| Fifth | 7 cwt 3 qr 0 lb | 35 1/4" | A |

| Tenor | 10 cwt 0 qr 0 lb | 39 1/4" | G |

The clock bell (weight: 2 cwt, diameter: 21", note: B flat) is also by John Briant. It was made in 1798 and bears the name of William Killingbeck, Churchwarden. It was hung for many years in a spire-like lion frame of 1848 which crowned the tower. Parts of the clock itself date back to the 17th century. In 1800 John Briant charged £10 for "Repairing and fixing C. Clock". It was restored by Thomas Safford of Cambridge in 1811.