St Mary's Church

Before entering St Mary's, admire the fine tower in flint and field stone, square at the base, rising to an octagon lit by round-headed Norman windows. Notice the attractive patterned stone bands above and below the octagon stage. In the 13th century a sixteen sided section in two parts, with narrow lancets, was added. And in 1964 a top band of 48 arches and a stainless steel spirelet with a 'Queen of Heaven' crown (commemorating the lost medieval spire) completed the tower as we see it. The architect was C J Bourne, who is remembered by a gargoyle on the tower (see Appendix 5).

The 15th century perpendicular gothic porch is now but a shadow of its former glory. A west, as opposed to a north or south, porch is a noteworthy feature and is sometimes called a Galilee. Before the Reformation the civil part of a marriage took place outside the church in front of witnesses and a porch would give them protection. This porch originally had a fan vault (Pevsner) in the middle of which, according to Cole, were carved the Tothill arms "held by an angel". The porch was presumably a gift of the Tothill family.

From the base of the tower look up to where there was originally an upper room, possibly for the use of bell ringers. In the 15th century this was reached by the stair turret in the north west corner, lit by primitive slit windows, or 'loops'. As the tower is now open to the top, it is possible to see how the builders made the transition from square to octagon by means of the shoulder-like 'squinches'. Notice the two 'kaleidoscope' stained glass windows, the one to the north made from 19th century remnants after windows were transferred from St Cyriac's to St Mary's, and that to the south from fragments of glass of about 1480 found on the sill of the eastern tower window during restoration.

The original 13th century font is now in a position which symbolises the entry of the newly-baptised into the Church. Before the restoration it stood at the west end of the north aisle. The plaque above the font rather touchingly commemorates the Allix family's nurse, Matilda Cole, where some of her charges must have been baptised.

The medieval stone coffin lid in the tower room was found in the south aisle, possibly where the Tothill chapel used to be. To the left and right of the great arch are the remains of what may have been 13th century altars (RCHM) hewn into the walls of the Norman tower. The prominent vaulting over the right hand one may have carried a canopy over a statue or a holy water stoup. Notice also the recesses in the west tower wall for a draw-bar to be inserted for security, and the two 13th century stone benches under the tower arch. After entering the church through the modern glass doors, see the plaque recalling the three young lives that they commemorate. There is a medieval scratching of an elongated head on the north reveal of the arch.

A look back

Before walking round the nave and aisles why not sit down and imagine them in previous times? The church we see today is a distillation of centuries of Christian faith and debate in England and reflects the current liturgy and the worship of the living Church in Swaffham Prior. The lights burning in the chancel and above the aumbry on the north chancel wall remind us of the perpetual presence of God, a symbolism shared with the Roman and Eastern churches. At the same time the simplicity and lack of ornament emphasise the protestant heritage - and the embroidered hassocks and stripped pine pews tell us that we are at the end of the 20th century.

The first church in this place would probably have been a small Saxon one built of wood, replaced in about 1100 by a narrow and probably dark, un-aisled Norman building with a small chancel. A wider chancel appears to have been added later in the 12th century to give extra space near the altar as the liturgy became more elaborate and more priests took part. Within the same century the great Norman west arch was formed to connect the nave with the new tower. Probably simple aisles were added in the same century. The position of a round-headed north door from this date can still be seen.

Between the 13th and 15th centuries there was a crescendo of liturgical richness accompanied by growing lightness and elegance expressed in the gothic style. The present north aisle and clerestory and the slender castellated pillars of the nave are restored 15th century work. How different this church would have felt in 1462, when one of its benefactors, John Tothill, died. Heavy with incense, glimmering with candles before secondary altars (one each in the north and south aisle chapels); the rolling cadences of the Latin Mass; an echoing stone floor; and much of the wall surface painted. It is hard to picture the wealth and brilliance of the medieval church, against which the protestant reformers set their faces. Yet in less than a century all this would have gone. The medieval screen separating the altar from the people was probably torn down and the painting obliterated; and the English language prayer book would have been in use.

Under Charles I and Archbishop Laud some of the old rituals crept back. So, in January 1643, William Dowsing was despatched into the Cambridgeshire countryside by Oliver Cromwell's general, the Earl of Manchester, charged with destroying all remnants of 'superstition'. Rails separating the Communion table from the congregation as well as any steps raising it above the chancel were particular targets. On January 3rd at Swaffham Prior, Dowsing's diary records that "we brake down a great many Pictures superstitious, 20 cherubims, & the Rayles we brake in peces and digged down the steps". The word 'Pictures' in Dowsing's vocabulary often denotes stained glass. Interestingly, however, the Latin inscriptions on brasses in the north aisle invoking prayers for the souls of Richard and William Water escaped destruction.

A hundred years after this devastation, in the mid-1700s, Francis Blomefield recorded on a visit to St Mary's "I find nothing in the chancel, it being just as old Dowsing left it". William Cole leaves a clearer picture: "the Chancel lies in a slovenly manner without any rails or steps to the Altar, but is separated from the nave by a neat screen over which are the Queen's Alms, and under them the creed, Lord's prayer and 10 commandments ... The old pulpit stands against the 1st pillar on the S.". This was the final outcome: rational, demystified protestantism based on the letter of the Old and New Testaments. The engine house of faith was the pulpit, not the table where Communion was seldom celebrated. At this time both churches were still being "upheld and maintained".

After another hundred years the wheel had turned again full circle. The 'godless' 18th century was remembered with a shudder as the new wave of church restoration began under the influence of the Oxford Movement and the Cambridge Camden Society. Altars, steps and communion rails were reinstated. New chancel screens were lovingly fashioned in medieval style. Not surprisingly, squire C P Allix, devout churchman and amateur archaeologist, was influenced by the new movement. Seeing the possibilities of the gothic ruin, he created the church we see today.

Squire Allix's St Mary's

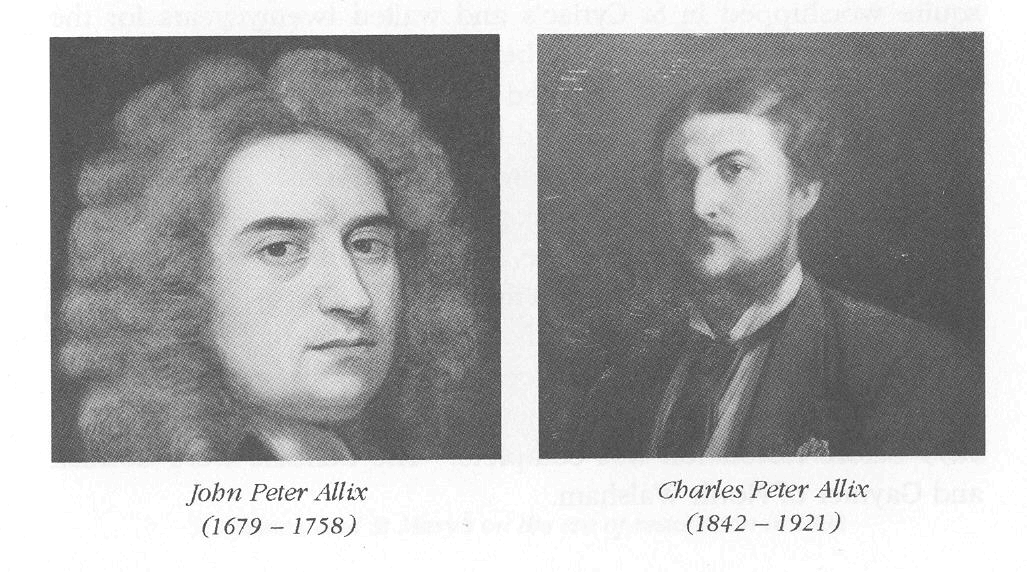

Perhaps this is the place to talk about the Allix family that so dominates this church. Much of their history can be read on the wall tablets and a simplified family tree appears in Appendix 6. Their ancestors had been important protestants near Alençon, Normandy, before they fled persecution under Louis XIV (see the brass tablet beside the screen). Perhaps Dean Allix of Ely became vicar of Swaffham Prior with a view to establishing a new family seat here in England. When his son Charles married the daughter of the Bishop of Ely, Catherine Green, the Dean promptly bought Swaffham Prior House from the Rant family in 1751 for the young couple to live in. In 1779 his grandson, John Peter, bought Baldwin Manor and Knights' Manor from the estate of their deceased owner, William Finch. By the time of Enclosure in 1805 the Allixes also administered Hall Manor, which still belonged to the Dean and Chapter at Ely.

Squire succeeded squire until the 1920s. None was knighted; none achieved great eminence, though one was an M.P. But they lived on their estate, they died and were buried in the village. When C P Allix died in 1921 the modern world was at the door and Lloyd George was in 10 Downing Street. Mrs Allix was driven by death duties to leave Swaffham Prior House. Their friend and vicar wrote in the parish magazine: "The Parish and Church which have benefitted through the residence of the family for centuries lose the genial and generous presence of their chief supporters; some of the best kind of citizens are banished; we doubt if there is any class in the world to compare with the old county families of England. It is easy to see now that the Parliament which introduced these taxes did much harm". In fact the heir, Charles Israel Lorraine Allix, continued to live in the village until 1960.

The Allixes had bought the ruinous chancel of St Mary's in 1810 to use as a family mausoleum. In 1878 C P Allix employed Sir Arthur Blomfield, a leading church architect, to renovate it and, with a view to complete restoration of the church, to build the present vestries and organ chamber with the tall entrance arch, and a crypt for a 'heating furnace'. The inner, locked, vestry was for the use of the vicar and was furnished with a small gothic fireplace for his greater comfort. The outer vestry was for the choir.

Blomfield was said to have "excelled in the charitable but remunerative art of keeping down the cost". But that was surely not all that recommended him. He was very much an establishment architect and churchman (son of a Bishop of London), a graduate of Trinity College and President of the Architectural Association. He designed Anglican churches for the Falkland Islands, Cannes, St Moritz and Copenhagen.

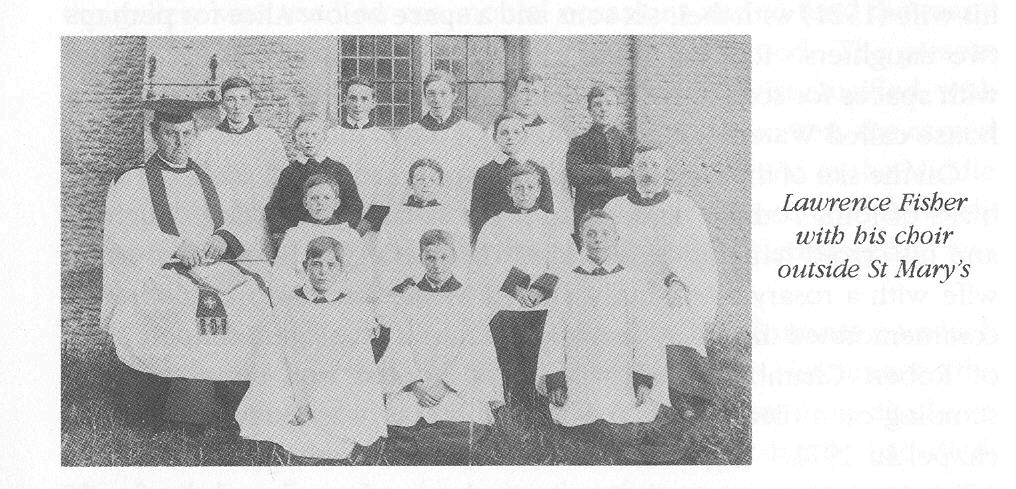

When the chancel was weatherproof, oak from the estate woods was put in it to mature ready for building the screen. Meanwhile, the squire worshipped in St Cyriac's and waited twenty years for the elderly vicar, Thomas Preston, to be succeeded by Lawrence Fisher in 1897. Preston was 81 when he died and it has been suggested that the squire considered his outlook old-fashioned and found the new 33 year old incumbent more of a kindred spirit. (Thomas Preston and his wife are buried in the south east corner of the churchyard, their stone bearing a carved anchor and rope. Lawrence Fisher's grave is in the new cemetery, in the 9th row on the left.)

Immediately after Fisher's arrival plans were afoot for the great restoration and a fund-raising brochure was produced. Blomfield's practice was employed again, though the architect himself died in 1899 before restoration was complete. The builders were Cornish and Gaymer of North Walsham.

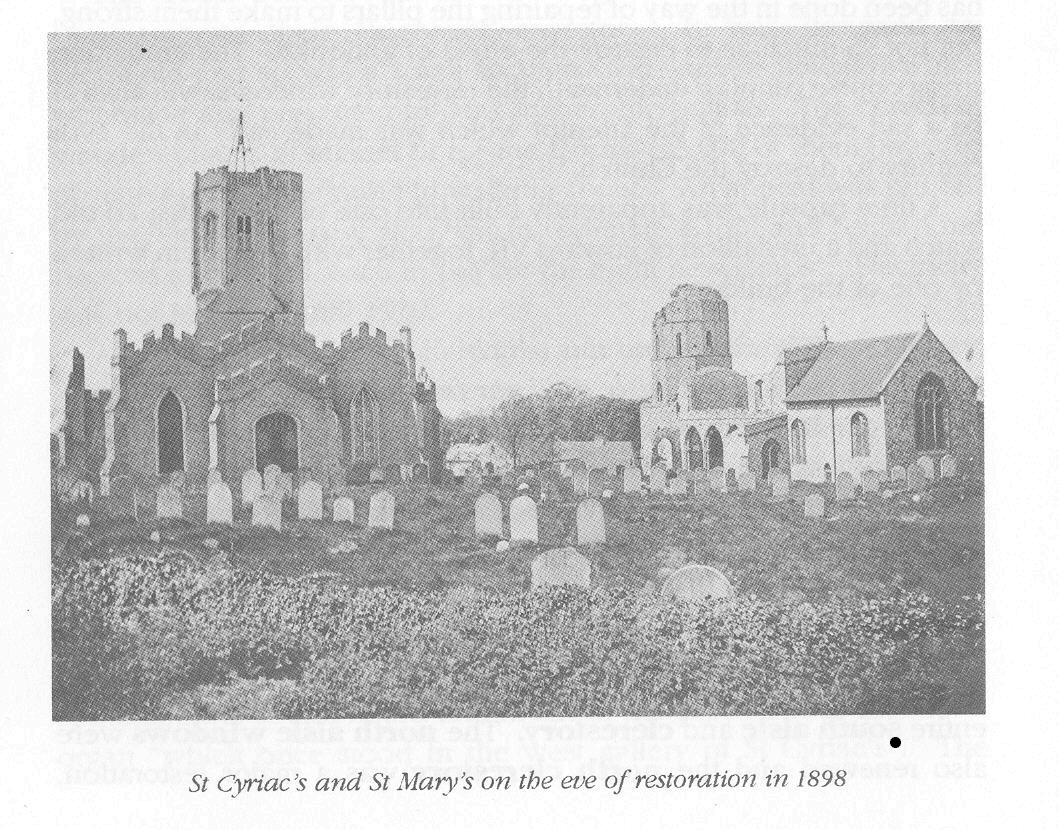

Justification, If any was called for, for abandoning St Cyriac's was that it too needed repairs and that in any case it was, in the words of Lawrence Fisher, "an almost grotesque travesty of a church, standing where once was a beautiful one". The wheel of taste had turned again. Swaffham Prior's parishioners were up to their old tricks, because they had two churches to juggle with.

The great repair

An early photograph (See page 21) shows the State of the nave and aisles when work started. They were roofless and the south aisle and clerestory had disappeared entirely apart from fragments at the south west corner and in the east wall adjoining the chancel. The restoration was completed between October 1901 and July 1902, exactly a hundred years after the disastrous demolition of the spire.

The vicar wrote, in his one-man parish magazine: "Everyone who sees the Church, now that the scaffolding has been removed from the inside, acknowledges that the work has been excellently carried out. The interior, as well as exterior, effect is beautiful, the old arches between the Nave and the Aisles, and the very old Tower Arch, together affording a dignity and grandeur not often met with. Enough has been done in the way of repairing the pillars to make them strong, but not so much as to destroy the effect of antiquity. The embattled string-course running underneath the clerestory windows, will always be a sad evidence of the attempt which was made early in the 19th century to destroy the Church".

A time capsule was apparently built into one of the pillars: an old

watch and a medallion of Edward VII, together with this poem written by

one of the builders:-

Whosoever find this watch

Which is neither slow nor fast

Must take it just for what it's worth

As a relic of the past.

In after years perchance this card

May be by masons found.

They in the springtime of their youth

While I'm beneath the ground.

The great chancel arch and the timber roof were new, as was the entire south aisle and clerestory. The north aisle windows were also renewed and the north clerestory was a major restoration, though it retained the original window shapes. (The obscure 'cathedral' glass used for the clerestory windows in the 19th century was replaced in 1995, admitting more light and solar warmth into the building.)

In the chancel, the east window and the two south ones were new, though they occupied existing spaces. The blocked round-headed windows to the north and south appear to be 12th century, as also may be the east wall. The north (vestry) door was new but the small south door is probably a 15th century one reinstated (RCHM). Of the first Norman chancel only a part of one deeply splayed window on the north side remains (notice the traces of paint). It was probably adapted in the 14th century to be a 'squint' from the north aisle chapel to the high altar.

The rood screen (1909) was a gift of the Allix family to commemorate their Huguenot ancestor. It was designed by Blomfield and so was a small lectern (with candle holders) which was made and presented by Mr Gaymer, the builder. The choice of wooden blocks of memel fir for the floors (13,000 of them) was "to obviate much of the noise in walking about". An appeal was put out by the Vicar for a new altar, organ (estimate £132) and "eight kind persons to give 18s. each to pay for the eight new lamps". Electricity was not installed until 1930.

A stone pulpit was offered by the vicar of Down Ampney, Wiltshire, and "gratefully accepted" by Mr Fisher. The architects, however, felt it was not good enough so it was put in 'Bullman's barn' until 1905 when it was passed on to St James's Church, Walthamstow. The present pulpit was brought from St Cyriac's. The IHS monogram stands for Jesus Hominem Salvator (Jesus the Saviour of Man).

Probably for lack of funds, the organ too was brought from St Cyriac's and set up in the chancel. It was rebuilt in 1925 by Millers of Cambridge. According to the parish magazine of March 1967 it contained the sound board and much of the pipework of the barrel organ "which once stood in the west gallery of St Cyriac's". The modern electric organ, which is more often used at present, was built by Colin Washtell, a parishioner from Reach, in the 1970s.

In 1916, the squire paid for the monumental slabs to the memory of the Rant family (his family's predecessors at Swaffham Prior House) and Martin Hill to be removed from the floor of St Cyriac's where those they commemorate had been buried, and set up in the north aisle wall. The cracked stone in the south aisle commemorating Sir John Ellys has made a double move, from St Mary's where he was buried "about the middle of the mid Isle" (Blomefield) to St Cyriac's and back. The last journey was paid for by Gonville and Caius college.

The pews were also brought from St Cyriac's. The vicar recorded that they were a "mournful brown" and so, together with the organ, they were painted green in 1902. They and the pulpit were stripped by members of the congregation in the 1970s.

Seating in the restored church was to be free to all corners, a situation the vicar found it necessary to explain to his flock. "It is with the greatest joy" he wrote "that the vicar is able to say that in S. Mary's there will be no appropriated seats. 'The rich and poor meet together: the Lord is the Maker of them all' - so says Holy Scripture. Whatever differences of rank there may be outside the Church, inside there should be none. We can understand that those who have had pews in S. Cyriac's may feel a little strange at first in not having appropriated seats in S. Mary's, but this feeling will quickly pass away. The right spirit of unity in worship is fostered by the feeling that we are all equal in the sight of Almighty God. In saying this we do not in the least wish to disparage the custom of individuals or families keeping to the same seats from Sunday to Sunday. Many persons like to do this for many good reasons, and no one would wish it to be otherwise. In fact it would be a nice arrangement if people would sit in S. Mary's as near as possible in the same positions as they occupied in S. Cyriac's".

The Allix family used to occupy the front pew on the south side of the nave. While the vicar almost certainly welcomed the new democracy, it was in fact urged upon him by the Incorporated Church Building Society which donated £130 to the repair on condition that all seating was free (see the tablet in the tower).

It must here be acknowledged that the saga of the great repair is inseparable from the personality of the vicar. He and the squire together raised the estimated £4000 required from the great and the good: villagers and friends of villagers, clerics, the Allix family and its relations, masters of Cambridge colleges and, once, a stranger on a train, from whom the vicar solicited a sovereign. On 13 April 1901 members of the 'Turf', who used to be able to see the old steeple from the grandstand at Newmarket, were urged to contribute in a letter from C P Allix to the Times. King Edward VII personally donated £10.

A walk around

In walking round the church, notice particularly the lack of substantial memorials or monuments. This is partly due to all the removals to and fro, partly to the lack of conspicuous wealth or nobility in the village in earlier times and partly to the Allixes' predilection for stained glass. 'Obituary windows' came into vogue in the 19th century. There is no doubt, however, that much has been lost and an indication of missing monuments is in Appendix 1.

All the stained glass windows are Allix memorials except the war and peace ones in the north aisle, which were conceived, designed and two-thirds paid for by the squire as a village war memorial in 1919. He also chose the design and position of the Celtic memorial cross, although the vicar had felt that "a large Cross in the Cemetery" was the right format. The glass in the south windows of the chancel was moved from St Cyriac's in 1878, 25 years before that church was finally abandoned. That in the south aisle was installed after 1902. A more detailed description of the windows is in Appendix 2.

There are early brasses, some of which have suffered with time and with rather careless treatment. In the north aisle, east end (called Water's chapel by Blomefield), are William Water of Reach and Alice his wife (1521) with their six sons and a space below Alice for perhaps two daughters. Richard Water and his wife Alice (1515) are shown with spaces for sons at his feet and daughters at hers. There is still a house called Water Hall at Reach.

On the site of the former Tothill chapel in the south aisle is a 1462 brass of John Tothill "armed cap a pe, standing on a dog couchant and his sword hanging before him" (Blomefield). Beside him is his wife with a rosary. Arbitrarily affixed to the same slab (which once commemorated the Drury family of Reach) is an elegant shaped brass of Robert Chambers Gent. (1638), a booted and spurred figure standing on a tiled floor. The Tothill chapel was made into a Lady chapel in 1971. The blue curtained south doorway had been the Allixes' private entry to their pew in the south nave and the family vault is under the chapel floor.

While in the Tothill chapel, read the inscription to Sir John Ellys. He went to study at Gonville and Caius College in 1647 as a 'sizar', a poor student who did menial work to earn his education. His family were Yarmouth merchants and though he shows a device of arms on his tomb (a mermaid with mirror and comb) he was probably not entitled to it. Unusually for a Cambridge fellow of the time he was never ordained. He served his college as an "eminent and careful tutor" for 45 years before becoming master at the age of 70. At this point he earned the epithet "the divel of Keys" because of his awkward and cantankerous attitude to the college Fellows, with whom he fell out disastrously. Ellys was knighted by Queen Anne in Cambridge in the same year as Isaac Newton - another awkward but prominent scholar not in holy orders. Neither man was of course married because college rules forbade this. Ellys's nephews and nieces buried him in Swaffham Prior probably to avoid the embarrassment of asking for a place in the college chapel. He was the owner of Tothill manor.

A small door in the wall adjacent to the cherub window to the north leads up to the rood loft, the gallery above the chancel screen. Rood was the word for cross in early English. Before the Reformation the gallery was used on ceremonial occasions and to tend the many candles which burned here in honour of the great rood. The present screen shows, as the old one would have done, Christ crucified, with his Mother and St John at the foot of the cross. The screen, the carved figures and the roof above were all colourfully painted in the Middle Ages. The ceilure (the narrow ceiling bay above the screen) is clearly marked by the spacing between the pilasters of the clerestory and was retained in the Victorian restoration.

High on the wall of the south aisle are four hatchments on which it is easy to pick out the Allix family wolf and spur. Hatchments (the word is said to be a corruption of `achievement') were arms displayed outside a house when a member of a prominent family had died. They were usually painted by a local craftsman or estate painter, are often primitive and not always accurate. Sometimes, after a while, they were hung in church. When a man is being commemorated, the arms are displayed on a shield. A 'lozenge' without a helm denotes a woman. The husband's arms are on the viewer's left of a divided device, the woman's on the right. For details of the families, see Appendix 3. Beneath the hatchments are two badly weathered inscriptions relating to Allix family members. In certain lights they are illegible, so the text is reproduced in Appendix 4.

Also of interest are two medieval piscinae (places where water from the washing of the priest's hands at the Mass was poured away). A 14th century one is in the south wall of the north aisle. Notice the drain hole. The other, a 15th century one, is in the south wall of the nave, close to the screen (RCHM). The stone recess to the south of the altar may have contained a wall monument. Another small stone shelf, probably for books, is behind the south choir stalls. A modern shelf behind the pulpit is supported on carved voussoir stones with chevron decoration from the original Norman fabric. One had found its way into someone's private possession and was returned during the restoration.